A shortage of competent teachers and too little money for large building investments are the main issues of the audited municipalities and districts, related to education financing. However, in the audited period the local governments fully discharged their obligations related to education, bringing up and care. Also, funds for that purpose were spent properly in most cases.

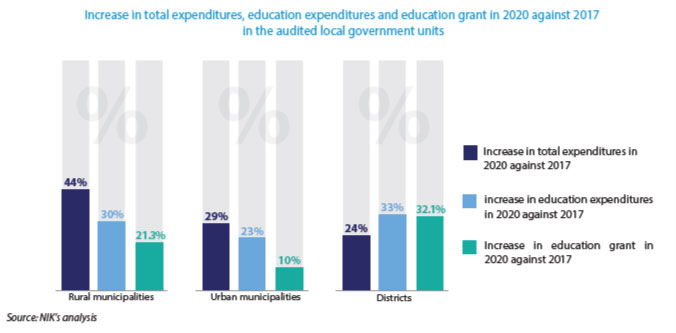

Education tasks are largely financed from the education grant. In 2017-2020, the amount transferred to local governments from the state budget was growing year after year. In case of municipalities responsible for the functioning of primary schools and kindergartens, and previously also lower secondary schools, expenditures for that purpose were going up even faster. In 2020, as compared with 2017, the education grant increased nationwide by nearly 20%, and the expenditures by 23%, whereas in case of local governments audited by NIK it was an increase by 23% and about 29% respectively. The biggest difference was noted by urban municipalities – in the audited period they reported a 10% increase in subsidies and a 23% increase in expenditures.

Graphic description

Increase in total expenditures, education expenditures and education grant in 2020 against 2017 in the audited local government units

| Type of local government unit |

Increase in total expenditures in 2020 against 2017 |

Increase in education expenditures in 2020 against 2017 |

Increase in education grant in 2020 against 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural municipalities | 44% | 30% | 21.3% |

| Urban municipalities | 29% | 23% | 10% |

| Districts | 24% | 33% | 32.1% |

Source: NIK’s analysis

All the audited municipalities and districts, apart from money from the education grant, which made up nearly 63% of the education expenditures, earmarked also their own funds for that purpose – they represented about 31% of those expenditures on average.

Graphic description

Sources of financing education expenditures (for all the audited local government units)

- Grant: 62.7%

- Own funds: 30.6%

- Subsidies from the state budget: 2.5%

- Other: 4.1%

Source: NIK’s analysis

The NIK audit showed that the biggest part of the education expenditures (as much as 50%) was earmarked for teachers’ salaries in the audited local governments. In 2020, the expenditures went up by about 30% on average, as compared with 2017. On the other hand, the smallest part of the education expenditures (5.3%) was represented by investments and modernisations in the audited local governments (although this demand was growing, especially in the municipalities being the “bedrooms” of large cities). Because of the influx of new residents, proper infrastructure needs to be provided there, including schools and kindergartens. It means that new facilities have to be built or the existing ones should be modernised.

Graphic description

Share of individual groups of expenditures in education expenditures in 2017-2021 (until 30 September)

- Teachers’ salaries: 50%

- Other current expenditures: 31.6%

- Salaries of administration and support employees: 13.1%

- Property expenditures: 5.3%

Source: NIK’s analysis

NIK audited 32 municipalities, 16 districts and 11 entities providing joint administrative and financial support to education facilities in 8 provinces. All of those local governments fully discharged their educational tasks defined by the law but the authorities of nearly 40% of them declared that if they had more money they could provide better learning conditions to children and also offer them extracurricular classes, psychological and medical care (including dentist care).

Education grant is growing but more slowly than expenditures

Local governments are obliged to perform the so-called education tasks, as part of which municipalities manage primary schools and kindergartens (until 31 August they were also running lower secondary schools), and districts are mainly obliged to manage secondary and special schools as well as school and care facilities. From 1 January 2017 to 30 September 2021, the audited local governments spent the total of over PLN 8.4 billion on those tasks.

Funds for that purpose came mainly from the state budget – the education grant with the education reserve totalled about PLN 5.3 billion at that time and increased by 23% in the audited period.

That was enough for the local governments to finance nearly 63% of education tasks (including 81.5% in districts, 50.5% in urban municipalities and 53.6% in rural municipalities). The majority of other needs related to education financing were covered by the local governments from their own funds which accounted for about 31% of expenditures in that area, 42.5% in urban municipalities and 40.4% in rural municipalities, and 12.5% in districts.

The rise in spending from the local governments’ own funds resulted mainly from an increase in salaries of teachers as well as administration and support employees, and also from the cost of financing replacements of teachers. Besides, more and more money was needed for afterschool care, maintenance of canteens and taking students to school.

Also, the number of children with statements of special educational needs or opinions of psychological-pedagogical counselling centres is growing. Therefore, there is a need to introduce and finance special forms of assistance tailored to such children.

Highest spending on salaries, lowest spending on investments

Half of education spending is made up by salaries of teachers who work in schools and kindergartens operated by local governments but also in other education facilities. All in all, in 2017-2021 the audited municipalities and districts spent on that purpose over PLN 4.2 billion, of which about PLN 0.9 billion was spent in rural areas, over PLN 1.5 billion in urban areas and over PLN 1.7 billion in districts.

The audit conducted by NIK in 48 municipalities and districts revealed a shortage of science and foreign language teachers in education facilities managed by 38 local governments. Municipalities and districts also had problems finding support teachers, having preparation in special pedagogy and being able to work with children with various disabilities or needs, such as autism, Asperger’s syndrome, impaired hearing, impaired eyesight or intellectual disability.

In nearly all districts there were problems finding teachers for practical vocational training in different specialties. According to the audited local governments reasons included not only the shortage of teachers in a given specialty but also low salaries which discouraged qualified teachers from working in school.

Investments are a significant burden for local governments. All of the audited municipalities and districts made some investments in the audited period, though. They included among others: construction, expansion and modernisation of education facilities as well as thermal upgrading of facilities or installation of photovoltaic systems.

In 2017-2021 (30 September), all the audited local governments spent nearly PLN 420 million in total on education investments. The scope of works in individual municipalities and districts was determined by their financial capacity. Rural municipalities spent most on that purpose – nearly PLN 202 million, districts - about PLN 131 million, and urban municipalities spent least – PLN 87 million in total.

To make those investments many local governments used the EU funds, the Physical Culture Development Fund, the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management or the Government Fund for Local Investments. As much as 46% of the audited local governments contracted a loan or issued bonds to cover the budget deficit partly or wholly related to the education investments.

Close-down of lower secondary schools

A significant change was made in the education system in the audited period. Gradual close-down of lower secondary schools started on 1 September 2017. That was related to the necessity to transfer students to primary schools. The reform chiefly fell on municipalities’ shoulders.

The NIK audit revealed that the schools liquidation costs were incurred by over 56% of the audited local governments – 10 rural municipalities, 14 urban municipalities and 3 districts. In case of municipalities those were mainly severance payments for laid-off teachers and support employees, also retirement benefits.

In most of the audited local governments the property after liquidated lower secondary schools, including buildings, was transferred to primary schools – already existing ones or the ones newly established in place of former lower secondary schools. It was not the case only in three municipalities. In some cases the buildings of liquidated lower secondary schools had to be adjusted to the needs of new schools.

Other costs of the liquidation of lower secondary schools were related among others to the purchases of equipment and furnishing for the existing and newly established schools.

More spending during the pandemic but also more savings

The education financing was also impacted by the COVID-19 epidemic. In 2020-2021 (30 September), nearly all of the audited local governments – 92% - incurred unpredicted expenditures related to the purchase of additional equipment for remote education, mainly laptops provided to schools for teachers and students. Additional expenditures – highly diversified – were also related to sanitary safety in education facilities.

Because of the epidemic, only 34 of 48 municipalities and districts received material aid from the government administration (mainly sanitisers and personal protective equipment). The majority of municipalities and districts also participated in the government programmes, as part of which remote education equipment was purchased. The programmes required the involvement of local governments’ own funds, though.

The COVID-19 epidemic resulted not only in unpredicted costs but also savings in some groups of expenditures. That was the case in all of the audited rural municipalities, 13 urban municipalities and 8 districts. It was no longer necessary to take children to school or organise catering for them. Also, during the epidemic teachers clearly worked less overtime, they also had fewer after-school or extracurricular classes. Some municipalities and districts also made savings on expenditures related to the maintenance of schools and kindergartens.

All of the audited local governments declared that in the period of remote education they monitored - via schools - the issue of digital exclusion of children and youth. Teachers verified students’ attendance in remote classes and in case of any problems or the lack of contact they intervened with the children’s carers. In case of no response, educational or probation officers were notified.

Because of children’s emotional and mental problems deepening during the pandemic, schools were also trying to provide students with psychological support in the form of regular duty hours of pedagogues and psychologists. Local government officials admitted, however, that they had problems hiring properly qualified staff.

NIK’s recommendations to the Minister of Education and Science

- a complex analysis should be made of local governments’ needs related to financing education investments;

- support of authorities managing public schools should be considered in terms of making repairs of education facilities and investments in that area;

- an in-depth analysis should be made of the teachers’ employment issue;

- system solutions need to be implemented to eliminate the problem of teachers’ shortage in case of some specialties.