Management of public debt and liquidity of the public finance sector

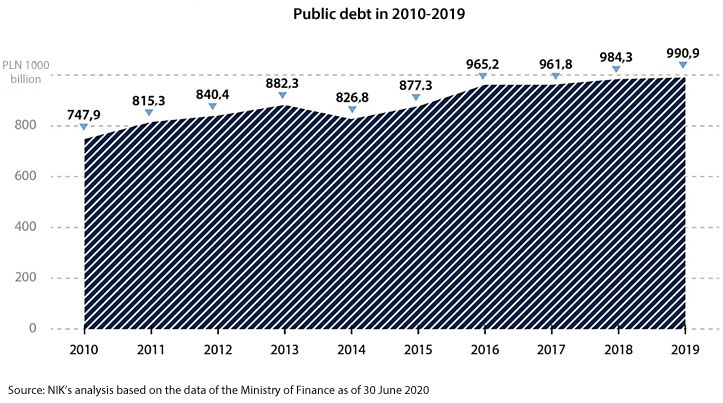

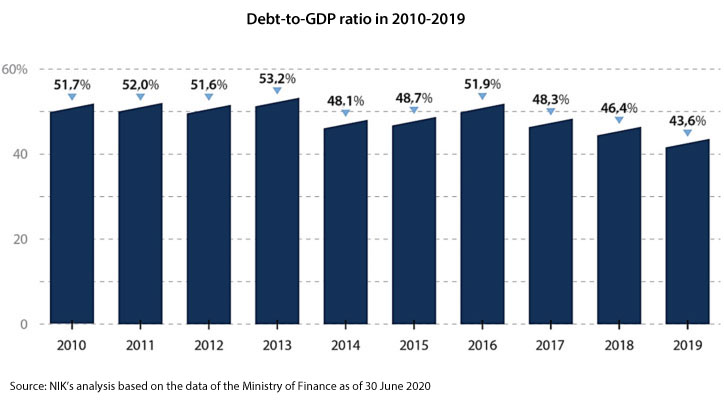

Before the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic, the public finance sector (except for some hospitals) incurred the public debt in a rational manner and repaid it on a timely basis. In 2014-2019, the debt-to-GDP ratio decreased by over 4 percentage points, which - considering the constitutional debt limit at 60% of GDP - provided room to finance the first stage of measures limiting the pandemic consequences. Further debt increase will be a challenge and so the sources and ways of its repayment will have to be specified. At the same time, the audited entities should improve the ways of minimising the debt service costs and depositing free resources in view of optimising benefits.

The NIK audit covered several years because regular state budget execution audits, due to their specificity, focused exclusively on one-year perspective. That time horizon prevented evaluation of the auditees’ operations in a longer-term perspective which should be the basis for system recommendations. NIK audited among other things how effectively and efficiently selected entities managed the debt. It should be stressed, though, that effectiveness means taking on liabilities in a responsible way to finance public services and repaying them on a timely basis, whereas efficiency is about minimising the costs of debt service and managing free resources in a profitable manner.

In the audited period, the Minister of Finance (2014-2019) and the audited local governments (2017-2019) effectively managed the debt, providing funds to cover expenditures and outflows, which included timely repayments of the maturing debt. Some of the audited hospitals did not achieve those results.

In Poland two debt calculation methods are applied

The public debt, calculated under domestic regulations, defines the debt of the public finance sector. This sector includes a closed group of entities mentioned in the Public Finance Act. Some entities, although they incur a debt to finance public services, are not part of that group. The public debt involves debt limits defined in the Polish Constitution and the Public Finance Act.

The debt of the public administration sector is calculated based on the EU methodology: the public debt value is corrected with liabilities of some entities considered as being part of this sector. Other corrections result from a different scope of the debt in question. That methodology forces the public debt recognition.

NIK numerously recommended liquidating that ambiguity. In that way the potential uncontrolled increase of the debt not recognised in the debt calculated in line with the domestic methodology would be limited.

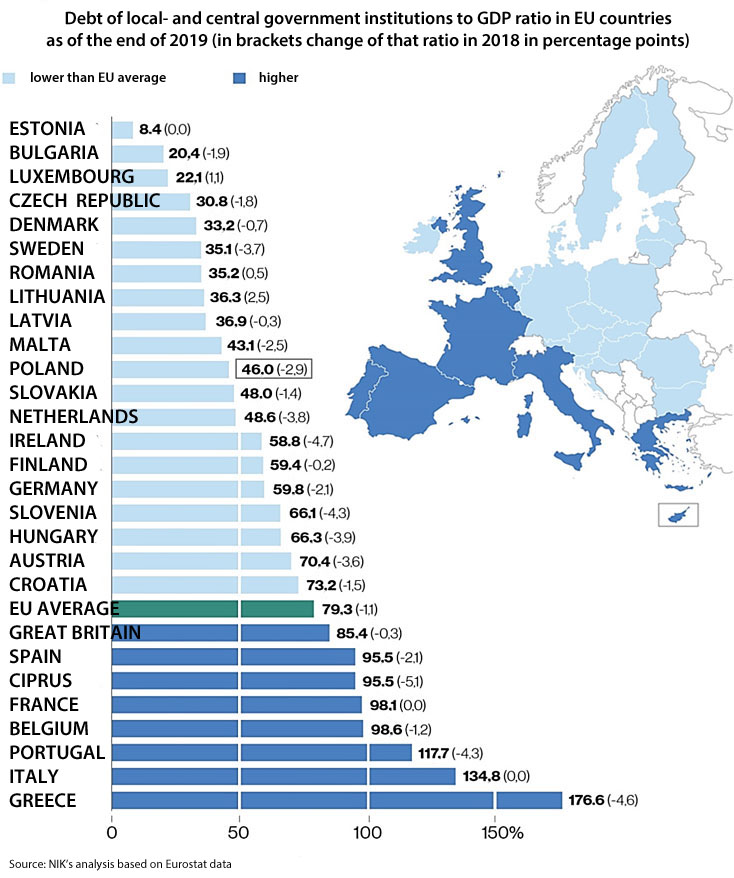

In 2014-2019, the public debt-to-GDP ratio decreased from over 48% to less than 44%. At the same time, the debt-to-GDP ratio of 46% achieved in 2019 in line with the EU methodology put Poland in a favourable position against other EU countries. The decreasing public debt-to-GDP ratio provided more space to finance measures limiting the pandemic consequences. It was the case thanks to the debt issue when there was a constitutional ban on taking up loans and furnishing guarantees as a result of which the public debt would exceed 60% of the annual gross domestic product. That margin may be too small, though, in the coming years if there is a significant GDP drop or if more debt has to be incurred for some important reasons. Therefore, the operative regulations limiting the public debt need to be reviewed in terms of their effectiveness, efficiency and impact on the economy.

The key role in the process of financing crisis prevention and management measures is played by the National Bank of Poland. It purchases bonds issued by the State Treasury, the Polish Development Fund (PDF) and Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego. In other words, the government anti-crisis programme is financed by the central bank. The NBP together with the government and related institutions created a closed circuit to launch some measures in this area. According to NIK, the government should evaluate the public finance condition to define in particular the impact of financing anti-crisis measures on the public debt level, its service costs and the credit reliability of Poland. It should be considered at the same time that in line with the assumptions of the anti-crisis shields part of the Polish Development Fund loans for entrepreneurs will be remitted. It is also important to develop a path to lower the debt-to-GDP ratio in the years to come as well the sources to provide funds for the debt repayment or refinancing, The NBP is independent from the government and it cannot be taken for granted that it is going to purchase subsequent issues of Treasury bonds.

NIK cannot confirm that the Minister of Finance acted efficiently by minimising the costs of servicing the State Treasury debt in a long-term perspective. The Minister failed to develop the method of measuring the level of achieving that objective and also he did not present any data confirming its achievement. According to NIK, the reason was that the objective was unaccountable.

In 2014-2019, the debt service costs were reduced considerably but NIK stands in a position that it was possible to incur a debt that would generate even lower costs while keeping the debt risk assumptions. The Minister failed to do it, though.

The Minister of Finance effectively managed the public finance liquidity, providing funds to cover all payments due. Whenever possible he also increased the level of bank deposits, securing unpredicted expenses, e.g. in case of a crisis. NIK has stressed that the Minister should not increase the level of his or her funds by the debt issue, if it is not justified by the economic situation. After all, borrowing money for that purpose cost more than the revenue from depositing those funds.

The Minister of Finance and the Minister of Family, Labour and Social Policy as the users of three special purpose funds, having plenty of free resources at their disposal, inefficiently managed their surpluses. They too often transferred them to low-interest overnight deposits (expiring in the morning, the following working day), instead of depositing them for longer periods to generate much higher interest revenue. A consequence was the loss of revenue in 2017-2019, which NIK estimated as at least PLN 24.6 million.

The audited local governments were trying to reduce the debt and its service costs. They selected the most acceptable offers and whenever possible replaced the debt which was more expensive to service with a cheaper one. Some of the audited entities did not make any optimisation analyses to choose the best financing instruments. The reason was they did not develop any debt management strategy or assumptions related to the debt portfolio parameters. Not all of them efficiently managed the surplus of budgetary free funds as they did not deposit them on the most advantageous terms.

It was worse with independent public complexes of health care facilities which operate under the pressure of unfavourable external conditions (an imperfect healthcare financing system). The majority of the audited hospitals had overdue debts from time to time. Some measures were taken, though, to restructure the debts and they were effective in some cases. On the other hand, the activities of health care facilities in terms of depositing free resources were not very efficient.

Both the Ministry of Finance and the local governments provided reliable information about the level of their indebtedness being part of the public debt. Some irregularities were confirmed in data coming from the hospitals but they were not very significant for the overall data on the public debt as their share in the debt was quite small. The Central Statistical Office properly discharged its duties related to the collection of data on the debt level. However, it lacked instruments to verify the data completeness, just like other data recipients at lower levels of the data collection system.

Recommendations

To the Minister of Finance to:

- review the domestic regulations limiting the public debt level in terms of their effectiveness, efficiency and impact on the economy;

- evaluate the public finance condition in the mid-term horizon to define in particular the impact of financing anti-crisis measures on the public debt level, its service costs and the credit reliability of Poland. This evaluation should also delineate the path of lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio in subsequent years as well as the sources of funds for the debt repayment or financing;

- initiate amendment to the Public Finance Act enabling local governments to quickly open budget accounts of the local government units in more than one bank to limit the risk of losing funds in case there is a presumption that the economic and financial standing of a bank will aggravate;

- impose an obligation on the units of the public finance sector to examine the completeness of reports aggregated by a given recipient by amending the relevant ordinance of the Minister of Finance;

- develop guidelines on effective management of free resources and address them to the entities having most free funds at their disposal. Those guidelines should help increase the value of funds transferred to the Minister of Finance as term deposits for the longest terms possible. That would improve the state budget liquidity by providing funds at a low cost and at the same time increase the revenue of state-owned special purpose funds.

Regardless of the above recommendations, recommendations were also addressed to the heads of the audited entities to eliminate the irregularities identified by NIK auditors.