Schools were not properly prepared for internal and external threats. In over 90% of cases, improper procedures were applied. Above all, they were not tailored to the realities of a given school, evacuation was carried out without taking care of the disabled persons’ needs, there was a shortage of adequate alarm devices. School employees had little knowledge of crisis management procedures. School management authorities did not get involved in implementing security procedures in subordinate schools, they did not verify their implementation or develop their own guidelines. Nowadays, schools are exposed to a range of diverse threats, such as dangerous objects found in the school, dangerously behaving students or parents, or even a bomb- or a terrorist attack.

Ensuring safety and security in schools is one of fundamental duties of school principals and teachers. Other responsible bodies are school management authorities, that is local government units, legal and natural persons as well as the Minister of Education. Various incidents and threats have become more and more common recently. There are media reports about brutal fights of students using dangerous tools, firearms brought to school or explosives planted there. Each situation of that kind requires an immediate response. Therefore, school principals and teachers should have mastered procedures in such cases. In crisis situations, there is no time to agree upon a strategy or define individual persons’ roles. Actions taken have to be adequate to the threat type. That is why, the procedures should be complex and deal not only with direct response to an incident but also with follow-up measures, such as taking care of the incident participants, gathering and passing information about the incident, evaluating the situation and drawing conclusions. What is important, the procedures have to be mastered by school employees and systematically practised. In 2017, the Ministry of National Education developed a document (updated in 2019 and 2020) called ”Safe and secure schools. Threats and recommended preventive measures in terms of students’ physical and digital security”. The document not only sets out preventive measures and procedures related to ensuring students’ security but also specifies a range of good practices and guidelines to be applied by school principals.

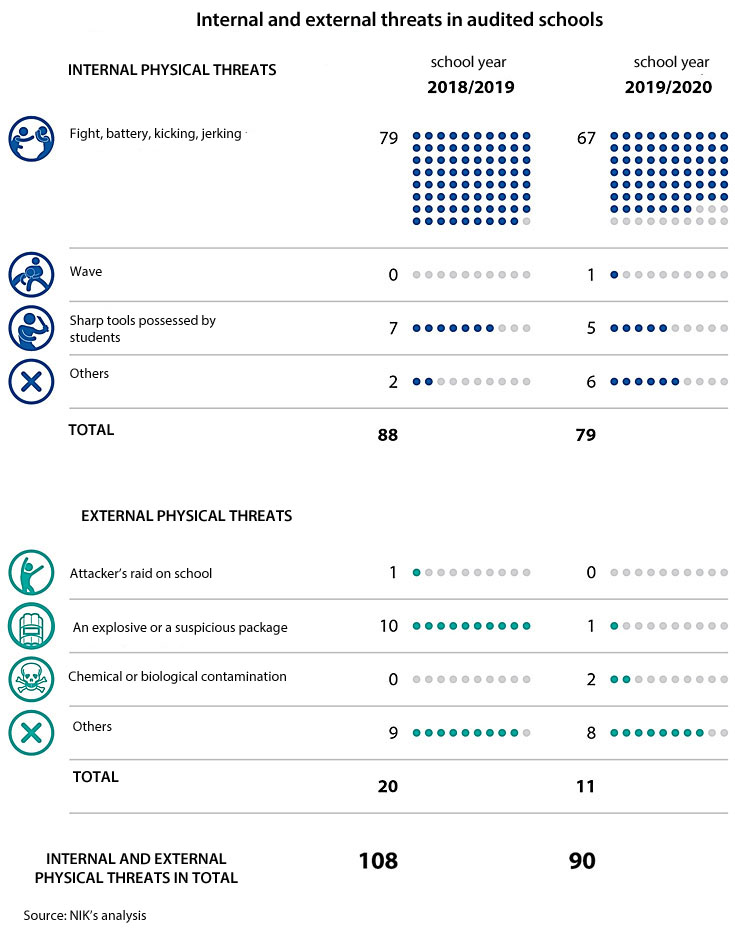

Statistically in all 377 schools managed by the audited authorities in both school years 2018/2019 and 2019/2020 (including the school closing from 16 March 2020 because of the pandemic), about nine incidents posing a physical threat took place every day. Usually those were fights.

Key audit findings

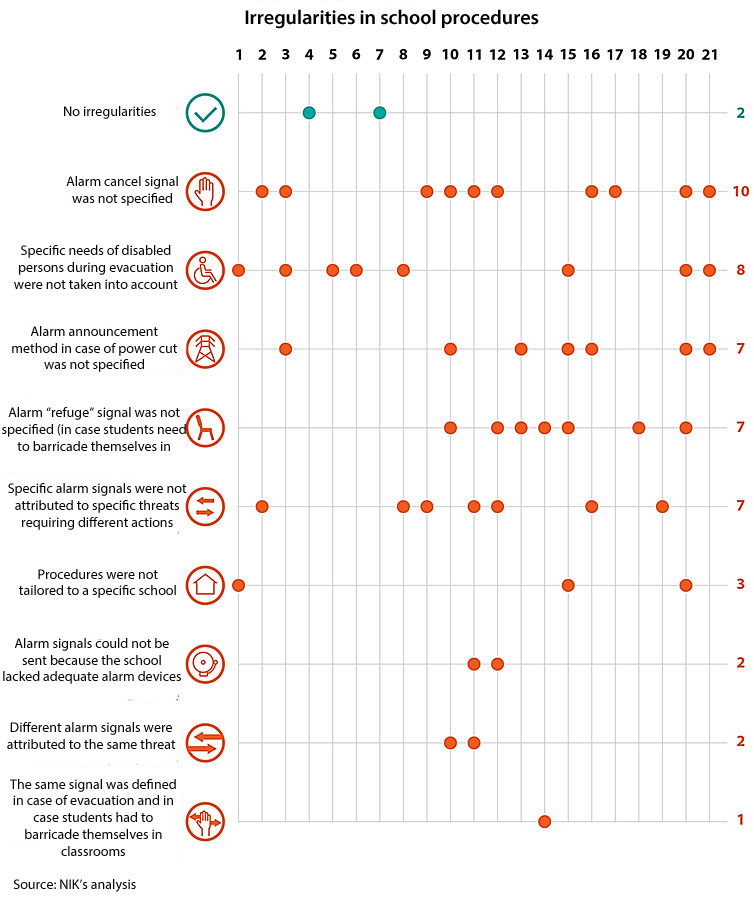

In all 21 audited schools, safety and security procedures were implemented in case of an internal or external threat. In 18 of them, the procedures were modelled on the manual ”Safe and secure school” developed in the Ministry of National Education. However, in 19 schools the procedures were not prepared correctly.

In each school (with one exception), principals made their employees and students familiar with effective safety and security procedures but that knowledge was verified in 16 schools. Only in three schools practical exercises were carried out.

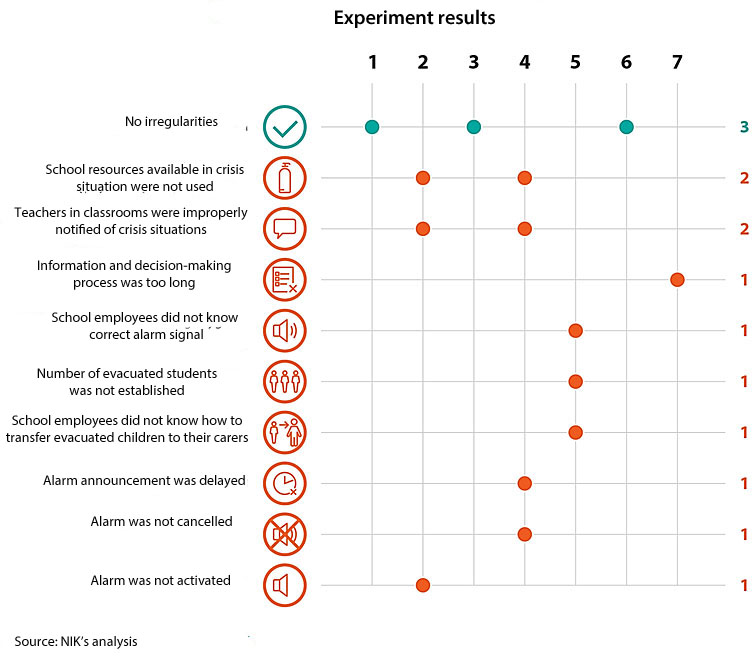

In seven schools, NIK verified practical preparation of personnel for a crisis situation. An experiment was made with participation of specialists appointed by NIK. In six schools, the raid of an armed attacker (so-called active shooter) was simulated, whereas in one school - a bomb incident. The simulation was made without evacuating persons staying in the building and without notifying relevant services.

Only in three schools, their employees taking part in the experiment were familiar with effective procedures in case an armed attacker raided the school. They acted in line with the principles defined there and their decisions were adequate to the threat type.

According to NIK, part of confirmed irregularities resulted from the lack of regular practice.

In most audited schools (17), their principals organised the threat identification training for school employees. The training programmes covered, among others, issues related to terrorist acts. In the remaining four schools, no training programmes were provided. One reason was they were not mandatory and the other - the schools had no money for that purpose. The school management authorities paid only for essential, mandatory training programmes, such as first aid. Despite the legal obligation, not all employees underwent the first aid training. In the remaining 18 schools, the training programmes covered the whole personnel. NIK has pointed, though, that in seven schools, from three to 10 years passed from the last training. After all, as regards first aid, current knowledge and systematic practice are equally important. Only that will help achieve the goal, which is to ensure school safety and security.

In the audited schools in school years 2018/2019 and 2019/2020, 198 incidents related to physical security threats were reported. Those threats occurred in 18 schools. NIK stated that the school principals and employees reacted properly. The most frequent cases of internal physical threats were fights and the possession of dangerous tools, such as a (pocket) knife. In such cases relevant school employees (principal, psychologist, pedagogue, class teacher) talked to the perpetrators and schools called in their parents. In justified cases (e.g. repeated undesired behaviours of students) schools also notified the Police and started cooperation with the family court.

The most frequent cases of external physical threats were bomb alarms, chemical attack threats and threats of penal acts against female students. In such cases schools acted in line with safety and security procedures, e.g. after receiving information about a bomb planted in the school, they started to cooperate with the Police.

NIK had numerous reservations about the condition of physical protection against threats. Only in 5 schools, no derogations from the condition set out in the law were reported.

The most common derogations were related to:

- exit routes were not consistent with the plan, some were not marked properly,

- emergency evacuation plans in some cases were not visible or even non-existent,

- some school rooms lacked medical kits, expired medications were kept in some of them, others did not contain the first aid manual;

- fences surrounding schools were damaged.

An issue was also using the monitoring system only for evidence, not intervention purposes. That was the case in 10 out of 21 audited schools. The image sent from cameras was not analysed in the real time, so the monitoring system could not be used to manage a crisis situation. The camera images could be played back after an incident (e.g. a fight). Then it would be too late for a school employee’s intervention. NIK already indicated that irregularity in the 2016 audit: ”The use of video monitoring in schools and its impact on students’ safety and security”.

School principals had no support from school management authorities (towns/ cities, communes, districts). None of 14 bodies covered by the audit developed any guidelines, standards or procedures to guarantee school safety and security. Also, none of them helped the schools develop procedures in case of an internal or external threat. Only two school management bodies verified how the threat response procedures were implemented. Five bodies identified threats but only two of them used expert analyses and studies. The threats included:

- school buildings were not properly protected against the entry of third parties,

- video monitoring systems in schools needed improvements,

- there were gaps in the schools’ fire protection system.

According to NIK, the schools’ principals were left without essential support which led first of all to the low quality of procedures implemented in schools in case of an internal or external threat. In the opinion of the school management authorities, it was the responsibility of school principals to ensure safe and secure conditions for work and education in schools.

The Ministry of National Education deserved a positive rating. The Ministry not only prepared and distributed among schools the manual ”A safe and secure school” but also coordinated the execution of tasks as part of the government programme ”Safe and secure+” (2015-2018). Then it also participated in a new, broader programme ”Safer and more secure together” (2018-2020).

Recommendations

Following the audit, NIK made the following recommendations:

To the Minister of Education and Science to:

- work out standards and good practices related to the operation of video monitoring systems in schools as an element of the school security system,

- de lege ferenda proposal: the ordinance of the Minister of National Education should precisely define the frequency of first-aid training programmes for teachers.

To school management authorities to:

- provide safe and secure conditions for education in the audited schools, especially by developing model procedures/ guidelines, including the use of video monitoring systems for on-going surveillance,

- get involved in developing security procedures at the school level and verify their implementation.

To school principals to:

- tailor security procedures to school realities and needs of disabled persons,

- eliminate irregularities from effective procedures, particularly with regard to alarm signals,

- systematically conduct exercises verifying practical knowledge of procedures related to identified threats,

- ensure on-going surveillance of CCTV images, at least during lesson breaks, when the risk of undesired incidents is the highest.