In 2014–2019, the number of foster families went down by 6%. The number of non-professional foster families dropped by 8%, whereas as for related foster families it was 7.3% less. On the other hand, the number of professional foster families went up by over 7% and in case of family foster homes it was about 69% more (although there are still relatively few of them).

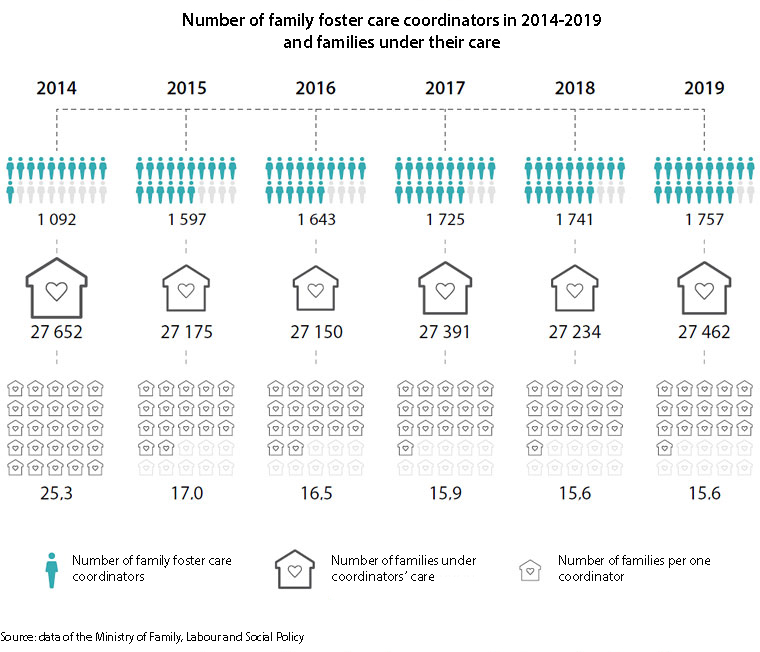

For essential family support, as part of the Foster Care Act of 2012, the profession of family foster care coordinator was introduced. They should, as an intermediary link, ensure possibly full support from the district family assistance centres (DFAC) to foster families and family foster homes. The number of hired coordinators in 2014-2019 rose by about 61%, whereas the number of children placed in family foster care facilities (in the same period by 3.4%).

Adequacy and effectiveness, and even the purpose of tasks performed by family foster care coordinators have not been examined so far. NIK has underlined that both foster care organisers and coordinators themselves come across many barriers. Therefore, looking into the coordinator’s function could help make essential system changes.

Too small number of foster families and family foster homes is the biggest issue. Other problems include lengthiness of court proceedings and inability to place e.g. multiple siblings in one foster family or family foster home. Sometimes foster families and family foster homes are overfilled, which results among others in limited contacts with biological families. Moreover, social welfare centres are not fully involved in work with the biological family (or are not involved at all). Frequently, access to specialists (e.g. child therapists or psychiatrists) is hindered and the number of psychologists is too small (because of low salaries).

The shortage of foster families entails the need to implement the central database about family foster care vacancies (which NIK already recommended 4 years ago). That solution would support the system transformation to underpin it in the first place with family foster care facilities and limit the role of educational care facilities.

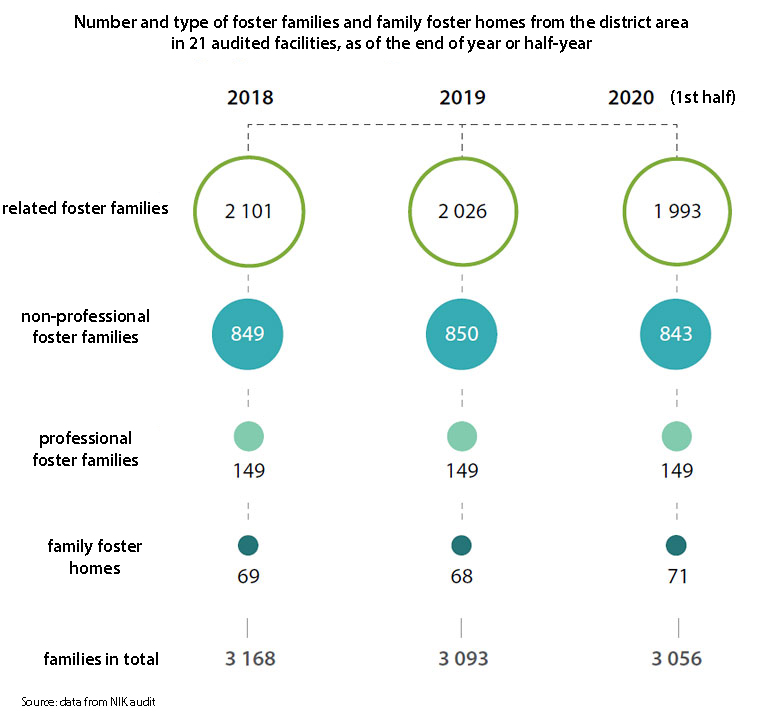

Nearly 77% of foster families considered coordinators’ activities as completely or partially necessary and effective. This is particularly important in the context of deficit of family foster communities and declining interest of individuals to take up that role. At the end of the first half 2020, related foster families made up the highest percentage (over 65%). Then it was non-professional foster families (nearly 28%) and professional foster families (about 5%) and family foster homes (over 2%).

In 21 audited districts, the number of foster families and family foster homes dropped in the audited period by 3.5% (from 3168 in 2018 to 3056 at the end of June 2020) – mainly following the decline in the number of related foster families. Throughout the entire audited period, the number of professional foster families remained at the same level and the number of family foster homes increased slightly:

On average, about 80% of foster families were taken care of by foster care coordinators (from 60%-99%, depending on the district). In the majority of cases, coordinators performed their tasks properly. However, some irregularities and the absence of a method of evaluating efficiency of coordinators’ activity could have had an adverse impact on foster communities provided with coordinators’ assistance and children staying there.

As a rule, support provided by coordinators was effective. In problematic situations they talked to foster families and children. Also, they organised assistance tailor-made to meet the needs of persons under their care. Effectiveness of coordinators’ activities ranged from about 92-99%. Ineffective measures usually included abandoning attempts to obtain child support or delayed motions to competent court to issue orders concerning charges.

An anonymous survey shows that in most cases coordinators actively helped their charges achieve all or most objectives – only about 5% of respondents said that coordinators did not participate in activities related to the child assistance plan. One of coordinators’ basic tasks are home visits which were held once a month on average.

Cooperation between coordinators and foster care organiser’s employees with external entities was related to contacts with family courts (concerning the possibility of children coming back to their biological families), adoption centres (concerning children with clear legal status given up for adoption), social welfare centres (obtaining information on biological families) and schools (monitoring children’s educational progress and behaviour).

Only in 4 of 21 audited districts, family foster homes and foster families were given full opportunity to use their statutory rights. They were mainly about professional development training programmes and classes run as part of support groups. Specialist assistance was also provided (chiefly psychological advice – 60%, re-education support – 17.4%, rehabilitation assistance – 7.4%). In over 15% of cases other types of support were rendered: of pedagogues, speech therapists, professional advisors or lawyers.

Specialist assistance was provided mainly on an ad hoc basis, also long-term, if necessary – depending on the problem.

District programmes for foster care development were carried out but their effectiveness is questionable since the target values of most indicators were not defined. Such indicators were specified only in three facilities but they were achieved only in one of them.

As a rule, foster care coordinators met statutory requirements, and in most cases were hired in line with statutory provisions. Foster care organisers provided training opportunities to coordinators, which they used. In 9 of 21 facilities coordinators could not take benefit of clinical supervision. Also, they did not participate in training programmes on stress management and professional burnout prevention (reasons included little interest and high costs).

Funds earmarked for coordinators’ salaries as part of the ministerial programme could not ensure fair remuneration to them. Consequences included high turnover in this profession and unstable cooperation with foster families and family foster homes. As a result, in half of the audited entities the statutory limit of 15 foster families and family foster homes per one coordinator was exceeded. The Foster Care Act envisaged launching a programme to support coordinators’ employment. However, the programme was not launched in 2020, as was previously planned.

Coordinators ran documentation in a way preventing full verification of their work results. NIK has recommended implementing nationwide standards for coordinators’ work, to allow explicit interpretation of their work assumptions, competence and activity framework, which is particularly important in case of serious problems with children and possible court proceedings related to the adequacy of coordinators’ work and its monitoring on part of the organiser. Interpretation has been arbitrary to date, so the approach of different audit bodies has varied.

NIK also identified some irregularities in coordinators’ work:

- child assistance plans were developed for too long (in extreme cases, up to eight or even twelve years). In some cases they were not prepared at all;

- such plans were developed without participation of biological family assistance specialists or entities organising work with families;

- plans were not consistent with requests resulting from periodic evaluation of children’s situation;

- objectives were not consistent with actions;

- long- and short-term objectives were defined improperly or not at all;

- documents were not individualised;

- deadlines for evaluating children’s situation were not met;

- foster families and family foster homes were not provided with complete documentation concerning the child (although coordinators were obliged to do so);

- activities aiming to obtain child support due or to clarify children’s legal status were stopped.

More than half of organisers or foster families and family foster homes supported by them were not controlled at least once in 2.5 years by local government supervisory bodies (the controls should have covered family assistance and foster care system, including coordinators’ activity). The controls were limited to approving annual reports on the activity of subordinated entities or issuing authorisations to audit foster families and family foster homes. That shows that the control exercised by district management boards was insufficient.

Recommendations

NIK has made the following legislative proposals:

to the Minister of Family and Social Policy to:

- develop and implement task performance standards for coordinators,

- implement plans of work with foster families.

It is also essential for the Minister of Family and Social Policy to make an in-depth analysis to answer the question why so few potential foster parents are interested in becoming a foster family. Effectiveness and results of coordinators’ work need to be investigated, too. Besides, coordinators’ employment needs to be subsidised again as part of the programme Family assistance specialist and family foster care coordinator.

to family foster care operators:

- take effective measures to observe the limits of foster communities per one coordinator;

- meet the obligation to properly prepare the child assistance plan and make necessary modifications of that document. At the stage of the plan development, effective cooperation with competent institutions - especially with social welfare centres - is vital;

- meet the obligation to seek opinion of foster families or family foster home managers before designating a coordinator;

- run foster families’ documentation with due diligence;.

- formally implement internal regulations on the performance and settlement of tasks of family foster care coordinators.

- make sure coordinators submit annual reports on their work results;

- make sure foster families or family foster homes enjoy all their rights under the Foster Care Act.

To district management boards to:

- strengthen supervision over family foster care organisers, e.g. by more frequent controls;

- introduce measurable performance indicators for specific objectives and areas in district programmes for foster care development.