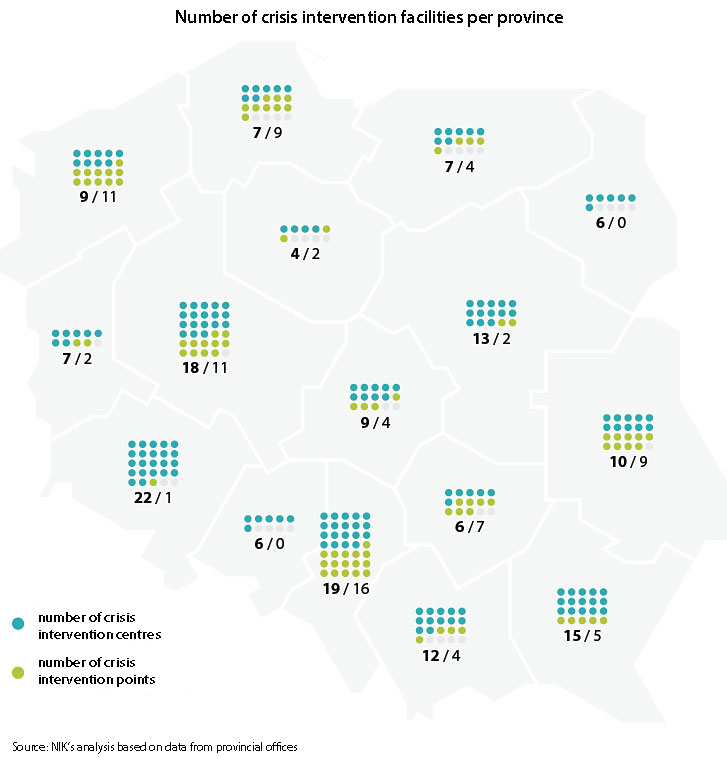

Currently there are about 170 crisis intervention centres operating in Poland. It means that 210 (more than half) local government units at the district level do not discharge their obligations under the Social Welfare Act. Crisis intervention points were opened in some districts or cities with district rights. In 2020, 87 points were in operation.

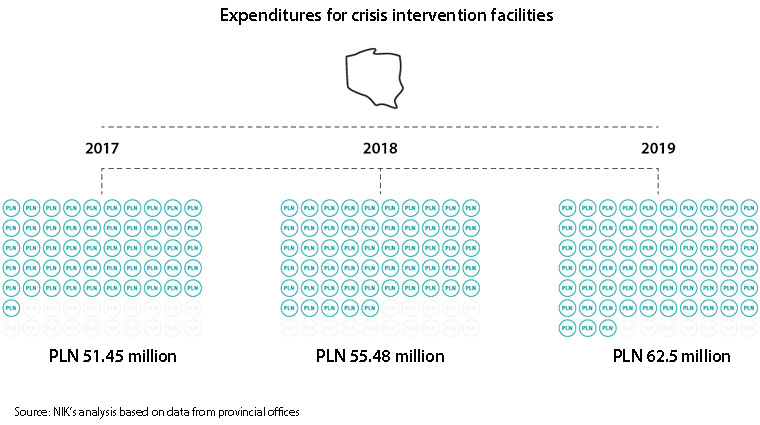

Funds earmarked for crisis intervention facilities were growing every year. In 2019, the total of over PLN 62.5 million was spent on that purpose.

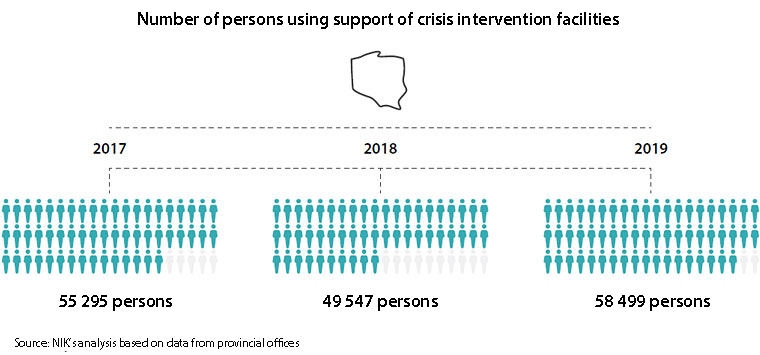

About 50 thousand people use the services of crisis intervention facilities every year.

Immediate intervention has become particularly important is the pandemic, in the conditions of growing social isolation.

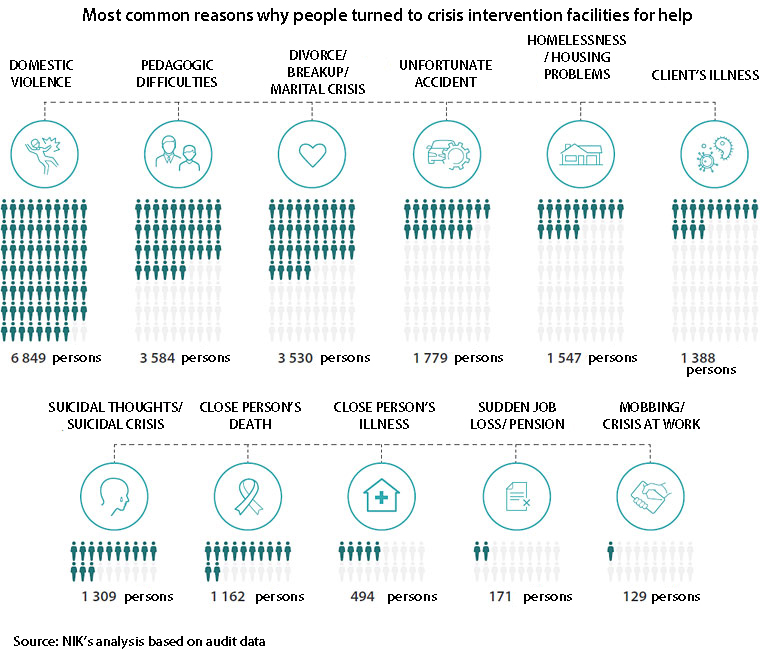

More than half of districts (55%) did not establish crisis intervention centres (CIC), although it was their statutory obligation. Additionally, only 30% of the audited facilities provided that kind of assistance 24/7, which in fact excluded immediate intervention assistance. Crisis intervention points (CIP) were established in some districts. Their operation was not specified in the Social Welfare Act, though. Crisis intervention points have been mentioned in the reports on the implementation of the National Family Violence Prevention Programme. However, nearly half of persons who contacted crisis intervention points, used their support for reasons other than domestic violence. It means that interventions made by CIP are not singled out in social welfare reports.

In case there is no crisis intervention facility in a given district, persons in crisis are trying to find it outside their district area. It shows how much this tool is necessary.

Low salaries are one of the reasons for the shortage of psychologists in crisis intervention centres. One facility did not hire any psychologists. Most facilities offered assistance only in their working hours. This approach does not meet statutory requirements because the needy do not obtain immediate, comprehensive and professional help in crisis situations. Because of the shortage of psychologists, interventions were often made by other specialists, e.g. social workers, pedagogues, family assistants or consultants. The assistance waiting time ranged from 5 to 41 days which is also against the idea of crisis intervention. Immediate support was provided only in big cities.

Measures addressed to children and youth were given up because of financial constraints. Heads of the audited facilities postulated that the activity of crisis intervention facilities should be subsidised from the state budget. But in spite of the practitioners’ voices, the Ministry of Family and Social Policy claims that this task should be financed in whole from local governments’ funds so it failed to develop any special programme to subsidise those facilities.

As a rule, the crisis intervention centres did not define any limits for individuals’ contacts with specialists. As a result, the support was more like long-term specialist assistance (longer than 10 years, in some cases), not a crisis intervention.

When providing this type of assistance, crisis intervention centres do the job of social welfare centres, mental health outpatient clinics or psychological-pedagogical counselling centres. According to NIK these forms of assistance should be qualified as specialist counselling.

As much as 90% of persons using intervention aid stated that the support was tailored to their needs, helped them considerably improve their life situation, develop psychological and social skills needed to handle difficult life situations. A great advantage of such facilities is their closeness to the place of residence of the people in crisis. The problem is, though, that not many people know that such facilities exist, because there is no comprehensive information concerning this area.

Crisis intervention centres popularised knowledge about crisis intervention and ways to handle difficult life situations. However, as surveys show, persons in crisis are mostly encouraged to seek support in crisis intervention centres by family members and friends, as well as representatives of courts, Police, psychological-pedagogical counselling centres or doctors. Over ¼ of the survey participants found information about crisis intervention centres on their own.

NIK points to the need for a nationwide campaign to popularise crisis intervention facilities which themselves cannot reach persons who may need help. The work of those facilities should be correlated with emergency communication centres operating in each province. This is particularly important in locations where 24-hour crisis intervention facilities do not operate.

Seven audited centres provided 24-hour assistance via telephone intervention lines which were active on all days of the year. However, most persons were not provided specialist psychological assistance because psychologists were rarely on on-call duty. In one facility, intervention phone calls were answered by security guards who were completely unprepared to provide this type of aid. Some phone calls were made by people with suicidal thoughts or even suicide attempts. That is why, NIK stands in a position that telephone intervention lines should be handled by qualified persons.

Public and legal assistance were also at a poor level. Public assistance was often provided by persons with other specialties and in some facilities legal assistance was not offered at all.

In over 60% of the audited facilities, specialists were hired under civil law agreements. This type of employment may not give them a sense of security or stability at work and so they may quit. The survey made by NIK shows that some of those people would prefer employment agreements. Besides, specialists hired under civil law agreements were not guaranteed any training programmes to develop their professional skills.

In November 2005, an amendment to the Social Welfare Act came into force, which liquidated payments for the needy who stayed in crisis intervention facilities. In four audited facilities, there were still resolutions in force defining conditions for such payments. In one of them they were charged.

Other flaws of the system included the absence of standards in terms of the facilities’ organisational structure and operation mode, minimum scope of services and qualifications of persons providing them. It is also related to the lack of supervision of the assistance quality. In 2017-2020, district family support centres controlled less than 22% of facilities.

Province governors also failed to make such inspections in 2018-2020, although they were clearly obliged to do so by the law.

All of the audited facilities developed plans to support persons or families in crisis, although in some of them the plans did not include specific objectives.

Assistance plans performance indicators were not defined in any facility. However, a great majority of facilities evaluated effects of the support provided by them.

Recommendations

To the Minister of Family and Social Policy to:

- define nationwide standards for intervention services with regard to the organisational structure and operation mode of crisis intervention facilities, minimum scope of services and qualifications of persons providing them;

- settle the legal status of crisis intervention points;

- monitor if districts meet the obligation to run crisis intervention centres.

De lege ferenda proposal

The Minister of Family and Social Policy should undertake a legislative initiative to amend the Social Welfare Act to enable extending the 3-month period of shelter for an individual or a family in a crisis intervention centre.

Recommendations to province governors to:

- make inspections of crisis intervention facilities;

- correlate emergency communication centres operating in each province with crisis intervention facilities from a given area, e.g. by providing emergency communication centres with 24-hour phone numbers. That would allow providing immediate assistance to persons in crisis, especially where 24-hour crisis intervention centres do not operate.

Recommendations to district governments to:

- run crisis intervention centres and make sure individuals or families in crisis are provided appropriate assistance by districts where this task is not performed;

- disseminate information about the possibility of receiving assistance as part of crisis intervention;

- make sure all specialists working in crisis intervention facilities are covered by professional development training programmes on crisis intervention and ensure professional supervision to those employees.