System recommendations and de lege ferenda proposals following the food safety controls have not been implemented to date. Therefore, NIK President appointed a special team which is expected to cooperate with experts from Polish universities on drafting recommendations to improve consumer protection. A major issue addressed during the conference was the dispersed and non-homogenous nature of institutional food control. Duties and responsibilities of various inspectorates overlap and are blurred at times. This leads to conflicts of competence. The institutional control is governed by many inconsistent legal acts. Provisions on establishing penalties for breaching food regulations are imprecise. These are main problems faced by the food control system in Poland. Fight against the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, also on part of the Chief Sanitary Inspectorate has become an additional challenge. That is why, NIK recommends handing over all competencies related to food control to one of the existing food control bodies or appointing a new, specialised inspectorate reporting to the Minister of Health. These changes would help effectively fight with the grey area of food production.

Another recommendation is related to the society education, showing a link between proper eating and health. Therefore, NIK suggests developing a spectrum of programmes and information campaigns addressed to all citizens. Advertisements which offer “wonder pills” should be extensively investigated.

Regardless of the system organisation, higher effectiveness and efficiency of the institutional control should be one of key goals. NIK also recommends active participation of Polish representatives in the EU legislative works on changes in the food safety supervision.

The improvement of consumer safety should be fostered by implementing recommendations from previous NIK audits. The key ones relate to an increased financing of food safety inspectorates, higher penalties for bringing hazardous food to the market, creating a system to evaluate the safety of food additives, especially the impact of their cumulation in a single food product. It is also important to expand pharmaceutical supervision exercised by the Veterinary Inspectorate, to control the use of medications on animal farms.

In 2017, the Council of Ministers adopted a draft Act on State Food Safety Inspectorate. Its assumptions overlapped with NIK’s recommendations. However, legislative works on the Act were not even started.

Extract from NIK's mega audit report - Food safety system in Poland – current status and desired trends

Competencies of individual inspectorates overlap, control authorities do not cooperate with one another, nor do they coordinate their activities. Supervision of animal slaughter is insufficient, which is partly caused by headcount issues in control authorities. The internet sales control system does not work properly, either. These are only some reasons why the food safety system in Poland is far from perfect. NIK has analysed the results of its nine audits conducted in the past six years, as well as the results of five audits of the European Commission concerning food safety in Poland. In cooperation with scientists, NIK has formulated recommendations to strengthen the system, improve food safety and thus increase consumer protection. As a consequence, NIK’s recommendations will have a positive impact on the overall health condition of the Polish society.

In recent years the Polish food industry has undergone significant transformations. Since 2010, the global production has increased by nearly 56% which was partly an outcome of joining the EU. Now the Polish food industry is one of the leaders in the export of food and agricultural products.

Considering the size of the food market and growing expectations of consumers, food safety is of key importance. In 2004, an EU regulation came into force, according to which any biological, chemical or physical agent in food or feed as well as the condition of food or feed potentially causing adverse health effects on humans is a hazard. These may be:

- food contaminants (chemical, physical, microbiological, radiological),

- food forging,

- inappropriate conditions of storing and selling food,

- inappropriate conditions of keeping animals,

- illegal activity related to food production.

A serious threat is posed by pathogenic bacteria in food products, resistant to most antibiotics. That is why, reasonable use of sanitisers by food producers, e.g. when disinfecting production machines, is so important. For that sake, testing should play a vital role in detecting (potential) pathogenic microorganisms in animals and in food. The law should also prevent frauds and food forging (e.g. using prohibited ingredients, offering low-quality products or selling food as of better quality).

The foods produced in Poland are subject to internal control (e.g. good practices of different kinds) and external control systems. External food control in Poland is exercised by several state–owned institutions: State Sanitary Inspectorate, Veterinary Inspectorate, Agriculture and Food Quality Inspectorate, Chief Plant Health and Seeds Inspectorate.

Additionally, the National Revenue Administration is involved in food import and export. There is also the Environmental Protection Agency in the food safety system which evaluates the condition of the environment, having direct impact on the health of animals and plants. The institutional food control system is also made up by authorities assessing food safety risks: the National Veterinary Research Institute and the National Institute of Public Health – National Institute of Hygiene.

The Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) facilitates quick exchange of information on food hazards among food control authorities in Europe. The member state in which a health hazard was detected, is obliged to notify other members which product it is about and what measures were taken to eliminate the risk. Authorities in the countries where the given threat occurred are obliged to take essential extraordinary measures, such as informing the public, withdrawing specific products from the market or making an inspection.

After the audit NIK repeatedly indicated insufficient supervision of authorities responsible for food safety and quality over the production process, distribution and trade.

NIK’s mega audit report on food safety system is a summary of nine audits of NIK and five audits of the European Union.

Based on the results of the said audits the following downsides of the food safety system and the control quality were identified:

Overlapping competencies and lack of cooperation among control authorities

Tasks and responsibilities of individual inspectorates often overlap and are not always clear. This leads to conflicts of competence in some cases. Cooperation and information exchange among individual food control authorities is not satisfactory. The structure of controls is non-transparent as it is governed by numerous legal acts.

Insufficient supervision of animal slaughter

In 2014-2016, the Veterinary Inspectorate failed to properly supervise the slaughter of farm animals, whereas supervision over farmers transporting their own animals was exercised only marginally. The Chief Veterinary Doctor had no information about the slaughter scale or inspections made by veterinary doctors. District veterinary doctors controlled home slaughters only sporadically (only two of 17 vets made single inspections). They were not familiar with the scope of provisions on animal protection, the scope of slaughter registration or qualifications of persons carrying out the slaughter. In January 2019, illegal slaughter of sick cows was detected. The auditors considered the control system as ineffective and not preventing from taking illegal actions. They emphasised that when assessing risks and planning institutional controls, relevant veterinary services did not take into account broadly available information on intermediaries looking for sick or injured cattle. The following audit revealed that the remedy plan was mostly implemented, the situation improved but a lot remained to be done, especially with regard to the transport of injured animals. The Veterinary Inspectorate and, to some extent, also the State Sanitary Inspectorate, are obliged to constantly monitor the presence of unauthorised substances and the content of antibiotics in food products of animal origin. They also oversee the trade and the way antibiotics are used in animal farming. A local audit of NIK showed that the supervision and control were not very effective. They did not indicate if the use of antibiotics was justified and if they were used properly. Besides, they failed to protect consumers from the consequences of inappropriately used antibiotics. The low effectiveness of supervision and control resulted mainly from the existing supervision model, the absence of adequate legal instruments or organisational solutions as well as the failure to develop principles of rational and safe use of antibiotics.

Illegal food production

The NIK audits showed that veterinary institutions failed to create the mechanism of revealing illegal activity by producers of food of animal origin. The Veterinary Inspectorate identified such cases mainly based on information from consumers or other economic trade participants, not based on their own survey. That was mainly related to the animal slaughter. Besides, the meat was often not tested for hairworm.

Following the NIK audit on admitting diet supplements to trading, it was found that next to the legal market of supplements, illegal supplements were in trade. They have questionable nutritional value and pose health risks. In the existing market conditions, more and more often original products may be replaced with falsified products. Obviously, in such cases their composition is completely out of control.

Staff issues in food control authorities

All the audited institutions in the audited period struggled with shrinking headcount and high staff turnover, caused mainly by too low salaries. One of NIK audits showed that in 2015-2016, the number of entities to be handled by one veterinary inspector ranged from 142 to 312. The auditees often had problems attracting professional staff, mainly veterinary doctors. Recruitment attempts were often unsuccessful due to low salaries. As a consequence, persons with similar or completely different educational backgrounds were hired as professional staff. This state of affairs was also confirmed by the EU audits.

Another issue is the still growing market of diet supplements. The NIK audit revealed that organisational conditions in the Chief Sanitary Inspectorate were not adapted to the size of the diet supplements market. There was a shortage of employees responsible for accepting and reviewing reports about bringing a diet supplement to the Polish market (or about intending to do so). In case of nearly half of the total number of reports received by the Chief Sanitary Inspectorate in 2014-2016 (about 6 thousand products) the verification process was not even started. In other words, no attempt was made to establish if those products are safe for consumers. Starting the product verification process was no safety guarantee for consumers. The reason was that it took about 8 months on average (up to 1.5 years) to start verification (from the date of filing the report), whereas the verification itself took about 15 months on average (over 2 years maximum).

The audit on admitting diet supplements to trading revealed that legal regulations were one of the reasons why the products were not properly brought to the market, why supervision of their health quality and trading was insufficient and why food education on those products was unsatisfactory. That is why, they did not fully protect consumers. It was particularly dangerous that non-verified products remained in the market for many years. Besides, as was found during the audit, the products often contained unauthorised ingredients, hazardous to human health. According to NIK, the existing reporting system, making it possible to bring a diet supplement to the market immediately after filing the report, poses a potential threat to consumer’s health or life.

Shortages in the equipment of control authorities and limited capacity for efficient food controls

Pursuant to the data of the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) for 2015, only 5.8 samples per 100 thousand inhabitants were collected to test pesticide residues in Poland. In the EU countries the average was 16.4 samples. Also the EU audit showed that the laboratory equipment of provincial sanitary and epidemiological stations was not precise enough and not sufficient to test all pesticides in domestic audit programmes and in the programmes of audits coordinated by the EU. One of NIK audits indicated that the sample testing times were really long (sometimes even up to 30 days). Such a long time made it impossible to withdraw products with short expiry dates from the market as they were already sold.

Also in 2019, due to financial limitations, as many as 47 of 50 samples were not tested for the migration of substances from plastic packagings to foods.

Inefficient internet sales control system and insufficient education and information about food safety

In the past years the internet sale, including food and diet supplements, has developed rapidly. The process was speeded up even more by the pandemic. The institutional food control bodies did not find this issue important. It turns out that the internet sale of some food types (including diet supplements) is specific, as people sell them from home where they cannot store goods. In those conditions it was practically impossible to collect samples for laboratory testing. Inspections were made only based on general procedures of the institutional food control. A separate issue that NIK noted already in 2017 was related to internet sellers who had their business registered outside Poland, also outside the EU, and who were bringing diet supplements to the market. In those circumstances nothing could be done to solve that issue. This made effective measures towards those entities impossible. No systematic or effective education and information activities on diet supplements or food additives were performed to develop proper attitudes and health behaviours in the society.

Hazardous food from Poland in RASFF (Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed)

In 2019, the number of alerts sent by the RASFF National Contact Point has increased significantly (203 in total, of which 48 about hazards). In 2017-2018, there were 87 and 131 alerts correspondingly. Most often they dealt with the presence of harmful bacteria in the Polish food. Unfortunately, in 2020 it was even worse. By 30 September 2020, the EU member states sent 273 RASFF alerts on the Polish food products. This is the highest score all over the EU.

The irregularities identified by NIK result mainly from the lack of coherent and effective system of supervision over the safety of food production and distribution. The Supreme Audit Office has repeatedly pointed to the downsides of the existing solutions, recommending activities which should bring about an improvement of the existing organisational and legal status. The system recommendations and de lege ferenda proposals, aimed at ensuring the optimal organisation of food control institutions – have not been implemented to date, though.

Recommendations for more efficient food safety system

The European Union did not dictate any specific model of institutional food control. However, most member states opted for some forms of consolidation of institutional food control structures. Poland chose the multi-institutional system. In the middle of 2017, the Council of Ministers adopted and submitted to the Sejm a draft act on the State Food Safety Inspectorate (SFSI). However, legislative works on the act were not started. The primary goal of the act was to create a new, integrated system to control food safety and quality. The only implemented change, consistent with the original draft act, was the standardisation of procedures for controlling food trading quality starting from 1 July 2020. The Agriculture and Food Quality Inspectorate took over that quality supervision from the Trade Inspectorate in retail trade. This measure should streamline communication on identified changes and speed up the decision-making process.

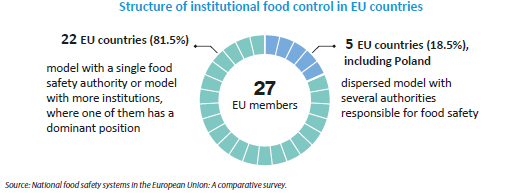

Graphic description

Structure of institutional food control in EU countries.

27 EU members, including:

- 22 EU countries (81.5%) – model with a single food safety authority or model with more institutions, where one of them has a dominant position

- 5 EU countries (18.5%), including Poland – dispersed model with several authorities responsible for food safety

Source: National food safety systems in the European Union: A comparative survey.

NIK's recommendations:

-

consolidating institutional food control structures

Consolidating the existing food control authorities and handing over the supervision to a single authority in a longer perspective should help make the institutional food control more efficient, effective and transparent. It should also simplify procedures, implement and use uniform principles of sanctioning cases of the food law infringement. This consolidation may considerably minimise the system weaknesses identified in the audits, or eliminate them entirely in some aspects.

Besides, the already complex situation related to food safety control was even more complicated due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Statutory provisions highlight the role of the Sanitary Inspectorate in the citizens’ health protection system. Despite great commitment and devotion of the Sanitary Inspectorate employees, the sanitary protection system may break down in the face of new hazards. This is related among others to long-term underfinancing of the said services, also to very low salaries, of field inspectorates in particular. The fight against SARS-CoV-2 has become a priority in the pandemic. According to NIK, this is an additional argument why state services focused exclusively on food safety should be in place.

-

educating the society on healthy eating

Healthy eating habits should be taught from the very childhood, chiefly in families. The role of schools is extremely important, at all stages of education. Broad-scale information campaigns prove necessary to spread essential knowledge and promote proper attitudes. Traditional and digital media need to be used for that sake. Considering the broad use of mobile devices, applications promoting proper eating solutions are vital. It is not only about convincing people to apply the healthy consumption model but also to counteract misinformation. The internet is full of fake news, after all. Proper education will help consumers to be more critical about advertisements which clearly impact food–related behaviours.

-

increasing efficiency and effectiveness of control activities

Activities taken by control authorities are insufficient in the face of numerous health hazards. Extensive controls of the food market are critical to identify and eliminate negative phenomena by appropriate administrative and penal sanctions which should be imminent, proportional to the breach of law and should have preventive and deterrent effect. They should also be enforced properly. The food market control needs to be based on efficient and quick actions. Immediate reactions to negative phenomena are crucial. Control activities of relevant services should also enable responding actively to advertisements.

-

taking measures to impact EU solutions

Internal regulations of the food market are largely determined by solutions adopted by the EU. In such cases the discretion of domestic authorities is limited. This is particularly noticeable in case of regulations on food additives. Therefore, NIK has stressed it is necessary to consider addressing the EU bodies to work out a joint, standardised methodology of gathering information on the consumption and use of food and to establish the limits of additives separately for the Polish market.

Also in the area of diet supplements the law is not fully harmonised. Differences in the approach to diet supplements, their definition, and above all legal provisions and principles defining that area, require taking adequate measures at the EU level.